“We lack adequate images. Our civilization doesn’t have adequate images.” — Werner Herzog

A gripping movie that doubles as potent commentary on our news media, Nightcrawler (2014) stands out as one of the more complex suspense pictures from the 2010s.

The movie is about so many things at once—the TV news business; journalism as a whole; entrepreneurship; employer-employee relationships; filmmaking and the rise of independent video production (e.g., Youtubing)—that I think it will end up exemplifying a lot of its era for future movie-watchers and historians.

In Nightcrawler, Jake Gyllenhaal plays Louis Bloom, a likely psychopath. Bloom, however, is a realistic version of a psychopath, the kind of predator you will run into in your own city, town, school, workplace, or church. He seems much more plausible than ordinary movie-psychopaths, as he’s not a vicious serial killer, outrageous super-villain, psycho-clown, or cackling maniac.

Bloom, however, is a realistic, amoral businessman, and he is vampiric—with his wide eyes, seductive words, turned-up collar, and sunglasses worn to protect him from the light. He flatters others to make business connections with them, tells small lies to make himself look better, and steals occasionally when he needs to beat his competition. He’s rarely violent in this movie; in fact, he manipulates other people into committing violence, for his own benefit.

The movie is about Bloom as a beginner in the independent video journalism business in Los Angeles. Independent journalists, called “nightcrawlers” because they work primarily at night, listen to the police scanner for accidents and crimes. When they hear about some major event that could end up on the news, they race through the streets to film it. Once filmed, they sell their video to local TV news stations in Los Angeles. The best nightcrawlers make great money by filming the bloodiest, most sensational crimes and tragedies.

Louis Bloom, who begins the movie knowing nothing about nightcrawling, aspires to be the best at it.

Gyllenhaal’s amoral character rings true to me. Ordinary psychopaths, sometimes also called sociopaths and labeled by psychologists as having an “anti-social disorder,” frequent our lives. According to the book, The Sociopath Next Door, by psychologist Martha Stout, psychopaths make up are about 3% of the population. (Stout calls them sociopaths, but in ordinary parlance, the two terms are interchangeable.)

This figure to me seems unbelievable, but even if 0.5% to 1% are “anti-social,” then at least 1 out of every 200-300 people are psychopathic, to some degree. Probably everybody, including you, has known a few psychopaths.

What is a psychopath, really? First, few are violent serial killers. To varying degrees, they don’t feel much if any emotion. They don’t empathize with others at all, and they don’t have a conscience. They don’t take responsibility for their actions, always giving excuses for why they failed or committed some heinous deed—just as Bloom does throughout Nightcrawler. (One of Bloom’s favorite movies is The Court Jester with Danny Kaye, as if he thinks of himself as the jester figure.)

Moreover, they’re manipulative and often charming. Theirs is a greasy kind of charm, an imitation of positive behaviors that generate trust and friendliness. These behaviors, because they lack a conscience, they use to their advantage. Note the occasional visual references to vampires in this movie, and the one verbal reference to the nightly news crew as the “vampire shift,” as if the vampiric Louis Bloom stalks others with his camera in the night, seducing them first and harming them later by filming them.

I think of psychopathy as operating along a spectrum, as many human behaviors and traits do. You’re not just either a psychopath or not one. Instead, the spectrum of psychopathy runs from an extreme end to a more ordinary one. At the worst end, you have your maniacs and serial killers, who (hopefully) are extremely rare and in jail.

On the other end, you might have someone who seems social and friendly, but at heart he’s a manipulative bastard. This is the kind of person who can function, and even thrive, in ordinary society.

In fact, it’s these latter, functional psychopaths who tend to rise up the ranks in society, becoming media figures, politicians, CEOs, and presidents of non-profit organizations. Supposedly, up to 20% of CEOs are psychopaths. If this is even half-right, a good portion of the people heading our institutions have psychopathic traits. Appearing to be friendly and charming, they are ruthlessly amoral, lacking much if any part of a morally-guided conscience.

So Louis Bloom, as a realistic manipulator who charms his way to business success, is a great representative character of our age. His chief goal is to become the head of a TV news network. As he tells Nina (Rene Russo), the station manager he becomes a colleague of, he doesn’t just want to be a journalist, he wants to “be the guy who owns the station who owns the camera.”

In my experience, high-trust groups are particularly susceptible to psychopaths. This is especially true of majority-Christian societies. Many Christians—remorseful when they are wrong; empathetic when they see others suffer; aspiring to always be generous and charitable—wrongly assume that others are just like them. (They are ignoring a cardinal law of life: beware of projecting yourself onto others.)

They are also sheep, ready to be preyed on by the proverbial wolf in sheep’s clothing. I’ve met enough people who seemed psychopathic in churches—and I have no ability to accurately diagnose anti-social disorders, so take this as an amateur observation—that I have found for myself an intriguing interpretation for Christ’s words about serpents in our midst. When he said, “be as innocent as doves and as wise as serpents,” and since the serpent in Genesis 3 was a deceiving, amoral maniac, I think we are supposed to think about how psychopaths think, in order to thwart them.

This is something that at least a good Roman Catholic, Lutheran or Calvinist, so aware as they are of the absolute horrors of original sin but also of the amazing gifts of God’s grace and salvation, ought to be able to do.

Louis Bloom, to me, is such a deceiving serpent. I say this while recognizing that I admire some aspects of him, given that he is, unfortunately or not, an exemplar of the Protestant Work Ethic.

Louis has what many of us want: the will to succeed. And also, the drive to improve himself at his craft, and the ability to persuade. He’s a tireless entrepreneur who becomes really good at video journalism. His business acumen is tremendous, when it’s being used properly.

But his employee Rick (Raz Ahmed), just like so many Christians I’ve met, makes a key mistake.

Rick believes that everybody has a fully-working conscience, just like Rick himself. People, Rick thinks, shouldn’t harm others. They should call the police when a crime is occurring. Yet, Louis doesn’t want to call the police when he’s filming a crime. He wants the crime to keep going, in order to capture the best and most sensational story he can record.

Rick trusts his boss too much, and even when he realizes very quickly that he should not trust him, he keeps working for Louis. Late in the movie, Rick labels Louis as “crazy.”

This label seems right at first, and in fact the movie encourages viewers to connect Louis to other crazy movie characters. The opening scenes of the movie, especially the one in which Louis asks a foreman for a job, visually quote the opening of Taxi Driver. Louis does seem like Robert DeNiro’s Travis Bickle character, but my read on Bickle is that he is schizophrenic and delusional. He has a conscience, but he rationalizes his violence so that his rationalizations assuage his conscience. These rationalizations overcome Travis’ inner moral sense, preventing him from stopping before he goes through with his murders at the end of the movie.

But Louis Bloom is not delusional, and Rick’s label of Louis as simply “crazy” is wrong, even a complete misunderstanding, for two reasons. The first is that Rick has no language and no conceptual framework for his psychopathic boss; he doesn’t seem to understand that a human could actually not possess a conscience. In short, Rick, like so many people I’ve met, is not aware of the anti-social disorder that 1% of the population has.

Second, Rick is the crazy one, in a practical sense. Rick remains as Louis’ employee, even though he’s not getting paid well and his boss repeatedly asks him to risk his life. If your boss is as unethical as Louis, then quit your job, as Rick ought to do. If your pastor is as manipulative as Louis, then leave your church for another one. Now.

Rick’s line to Louis, later in the movie, is telling: “You gotta talk to people like human beings. Cause you’ve gotta weird-ass way of looking at shit. . . . Trouble is, you don’t understand people.”

And yet Rick is lured in by the lucrative offer that Louis gives him, failing to understand that, to Louis, Rick himself is just a thing to be used and disposed of in pursuit of Louis’ goals.

Rick is a sympathetic character in part because his mistakes regarding Louis are reasonable. Although it’s a mistake to assume that other people are just like you, as I think Rick does, his is a reasonable mistake because civilization itself is built on trust. Absent that, there is no society. (Thus, Louis is truly anti-social, in that he’s acting to destroy the moral foundations of all societies everywhere.)

High-trust groups are susceptible, badly so, to Louis Bloom-types. They act too kindly, as innocently as doves, without studying hard the second half of Christ’s quotation. More of us need to maintain our innocence while thinking “like serpents” to know where we’re vulnerable and how we can stop them from preying on our communities.

Otherwise, we will continue to be prey for panderers, seducers, sociopaths, and pedophiles.

Louis’ line to a police officer encapsulates everything about him: “I like to say that if you are seeing me, you’re having the worst day of your life.” He means this in a sickly humorous way. Yes, you don’t want to be on camera when Louis is around, because you’re going to be at least badly injured, if not dead.

But this line is far more telling. Louis is an amoral vampire, a manipulative serpent, who looks and usually acts like any ordinary Joe. He’s telling you the truth: people like him are out to give you a bad day. To them, you are an object. Be on your guard for people like him, he reveals to us, for they are common.

The News Media is Psychopathic

What’s fascinating about Nightcrawler is that Louis Bloom isn’t really the major villain. That would be the local TV news industry in Los Angeles.

Nightcrawler is devastating in its portrayal of a news industry that preys on crime and accident victims, even before Louis Bloom becomes an effective nightcrawler.

The news industry depicted in the film is corrupt and amoral. Nina, the TV news station manager that Louis works closely with, relishes in bloody footage. She tells Louis that the best video for the news is “a screaming woman with her throat cut, running down the road.” Little does she know how attractive that image is to the psychopathic Louis.

Moreover, the nightcrawlers relish in getting the best footage of badly hurt or dying people. Joe Loder (Bill Paxton) is the professional nightcrawler whom Louis first meets and then begins to imitate. The first time that the movie introduces us to Joe, he delights that he shot great footage of the “five fatals,” an accident in which five people were killed that will make him a lot of money.

Nina and Joe, the professional journalists highlighted by the film, love blood for the sake of attention and profit. They want violent incidents to happen, so that they can profit off of it by showing it on the news. Louis watches them and simply imitates them, improving on what they’ve shown him.

Additionally, Nina only wants to show certain crimes on TV. If the crimes involve lower-class people, she doesn’t care, and instead she wants white suburban victims so that the right demographic tunes in, increasing her ratings. Once again, Louis listens to her advice and simply follows it.

Every time I have watched this movie, I come away with a deepest of convictions about TV news, and all print or video news in general, as actually promoting the things that they are warning us about.

Nightcrawler is telling us that journalism, as practiced today, actually encourages the creation of stories that promote social tension, fear, and violence.

This is a bitter pill for us all to swallow. Who doesn’t want journalism to be a noble calling about finding and exposing hidden truths? What about the ace reporters who risk it all to give audiences information about what is really happening in the world?

Nightcrawler says that that ideal not only doesn’t exist, it’s a delusion to believe that it does. Instead, news is about entertainment, first and last. The news business is a business, period. It craves profits, it needs ratings and viewers, and so it needs the events that can garner those viewers, for the sake of profits.

Of course it’s a cliché to say about the news that “if it bleeds, it leads.” Joe Loder says this to Louis during their first encounter. But one of the basic ideas of this important cliché is that all news is biased because it has to lead with something.

If news is a for-profit business that tries to capture the attention of ordinary people, then it will strive to lead with the most sensational story possible. Whether or not all publications indeed do this, the need to lead with sensationalism is a fundamental component of the news business. It’s in its essence.

Give journalism the highest possible standards, start it out on the highest ethical level, and over time it will still gravitate towards sensationalism and “fake news,” which is not even close to a new phenomenon.

To break into the lives of ordinary people, who always need to pay attention first to their local, personal cares and concerns, the news finds itself in competition with ordinary life. Our attentions are scarce resources. News stories that heighten fear, hatred, or other strong negative emotions work best to divert our attention towards the news media business, which helps it to be profitable, and away from our own lives.

The only things stopping our news industry from going all-out in reporting on only the most sensational stories are ethical limits.

But in Nightcrawler, ethical limits for journalists don’t exist. Repeatedly, minor characters try to bring up possible limits, which every major character dismisses. Rick tries to warn Louis repeatedly, as he expects Louis to call the police when he ought to, and to stop filming and to help victims of accidents.

But neither Louis or Nina ever do stop to help anybody.

The news system encourages Louis to break necessary societal boundaries. First, he gets very close to victims in order to film them. The police don’t enforce the 100-foot rule, where journalists are not supposed to get closer than 100 feet from accident victims. So that’s one law that Louis happily violates.

Next, Louis manipulates crime scenes to get better footage. In one, he moves a body. In another, he unlawfully enters a house (where a triple-murder has occurred!) and rearranges their belongings.

Louis keeps going. He doesn’t tell the police that he has film of the killers who committed the triple-murder, so that he can follow them around to capture more footage.

And then for the end: Louis actively creates a crime scene. He sets up the cops and the murderers to have a gun fight in a restaurant. Then he gets in a police chase, only to intentionally get Rick killed so that he can film him.

In short, what Louis is doing represents a damning message about modern journalism. Our news industry not only roots for tragedies to happen, it even creates those tragedies so that it can profit off of them!

Now, few want to think this way, as it feels too conspiratorial to be true. But movies have been telling us about this kind journalism-without-ethics long before Nightcrawler. In Citizen Kane, Orson Welles’ character as a young newspaper mogul delights in starting the Spanish-American war so that his newspaper can profit from it. In Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole, the journalist played by Kirk Douglas keeps his exclusive story about a miner trapped in a hole going, even though he could help that miner get out.

In my life, I’ve seen the news encourage nonsensical rifts between celebrities and between athletes, for the sake of ratings. If there’s no news that’s sensational enough to break into the lives of ordinary people, news media organizations will seek to create stories that are ultra-sensational. They don’t just find stories; like Louis, they make the stories happen.

Like you have, I’ve seen news media (on all political sides, mind you) perpetuate hoaxes and nonsense. One of those was the recent Russia-collusion narrative from 2016-2019, which turned out to be nothing but a three-year ratings-boost for fledging newspapers and cable-news networks.

I’ve seen the media companies—and this is worst of all for me—encourage wars. I remember Gulf War 1, in 1991, with CNN gleefully showing the bombing of Baghdad. Then the “shock and awe” of early 2000s Iraq war, predicated on the lie passed around by most in the news media that Iraq was involved in 9/11 and that there were WMDs in Iraq.

And the list just goes on and on, sickly and perversely, and on and on.

The tricky thing about interpreting Nightcrawler is that it’s not easy to tell if it’s criticizing just the local TV news industry in a major U.S. city, or whether it’s a movie that represents the decline of all of journalism. I believe that it can interpreted both ways, and I’ve assumed so here.

Regardless of that particular interpretive choice, the news industry depicted in the movie is certainly as psychopathic as Louis, in its amorality (i.e., lack of ethical standards) and in its desire for more and more business, at the expense of the lives of ordinary people.

No wonder that Louis flourishes as an up-and-coming video journalist.

The Cheap and Easy Business of Filmmaking

Nightcrawler depicts an entrepreneurship-tale that, absent Louis Bloom’s disturbing ethical choices, promotes entrepreneurship. It’s a rag-to-semi-riches story.

Louis begins the movie knowing nothing about nightcrawling, and by the end of it, in the movie’s final scene, his business has quadrupled in size. When he first tries to learn how to shoot film, he makes dumb rookie mistakes. He learns, practices, obsesses, and vastly improves his ability to produce great content.

This makes his business grow. The second act of the movie opens with Louis upgrading from a junk car to a red Dodge Challenger, and from a dumbphone to an advanced GPS system.

Louis also repeatedly talks about how important it is for his company to be successful. He achieves his goals. He tries many negotiating tactics, he puts himself in the right places to succeed, he uses his leverage to improve his odds of getting the best deal. We see him negotiate with Nina to get as much money as possible for his videos, but then he negotiates with his employee Rick to pay him as little as possible. Louis is always looking for the best bargaining position.

What does Nightcrawler say about the business world? Again, Louis the psychopath is on the track to success. He’s good at flattering and pleasing, and he’s also good at persuasive fast-talk.

Note that Louis’ specific job choice, filmmaking, is a crucial part of the movie. He starts an independent video production business. Since this movie was released near the beginning of the Youtube-era, a key transitional moment in the history of media, when anybody with a computer and Internet access can start an online channel, Louis is a fine representative of what Youtubers and other online channel-creators could become.

Anybody today, and even back in 2014 when the movie was released, can do exactly what Louis does, which is make videos of anything that anybody online might like, and then upload them. (Although Louis has to go through the gatekeepers at a TV station, Youtube makes it much easier to make videos of whatever you want and monetize it, as long as you don’t violate their terms of service.)

Is the movie slamming this new era of filmmaking? Not completely, I think, but it is warning us about what might happen if everybody in the world had the opportunity to become filmmakers, which they do.

Without sufficient ethical standards, such filmmakers could profit off of anything, including horrific crimes, as Louis does.

This is particularly emphasized in the last words spoken in the movie by Nina. Confronted by her assistant manager, she’s challenged about doing deals with Louis. Of him she says, “I think Lou is inspiring us all to reach a little higher.”

This is true if she means that Louis inspires us all to be success in business. But it’s also true another way. Several times in the movie, we see shots of Louis holding his camera up high above his head, in order to capture the best shot. Louis literally reaches high into the air to be a filmmaker.

So what Louis is inspiring us all to do, according to Nina, is to reach up high with our own cameras and take footage of anything sensational that viewers might be attracted to. In her words, Louis is a representative, independent filmmaker—he represents what’s possible for me and for you.

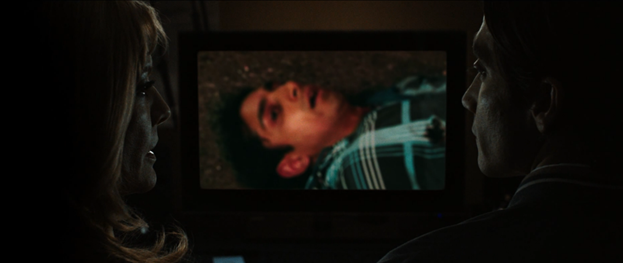

Are independent filmmakers psychopathic, as represented by Louis? I hope not. The other movie quoted often throughout Nightcrawler is Michael Powell’s controversial Peeping Tom (1960), about an independent maker of films that are entirely perverse and which he keeps to watch in his secluded hideout. At the end of the movie, Louis and Nina have a Peeping-Tom-moment, in which they perversely converse while they watch video of Rick dying.

For them it’s a romantic moment, while we watched, sickened by their twisted indifference.

What Nightcrawler knows well and assumes is that film is an odd medium that allows us to stare at something without the threat of being seen.

When we watch anything, we viewers are hidden, while whatever is filmed has been exposed to us. Powell knew the very dark implications of this, showing it to us in Peeping Tom.

Louis and Nina and the entire TV news business knows this, too. Their excuse might be: we are giving viewers exactly what they want, which is the ability to peer at events which appear simulated (on TV) and thus safe or even unreal.

Several times in Nightcrawler, director Dan Gilroy compares the real world to the simulated, produced world of TV news. He’ll show us the real world, and then he’ll show us the camera lens of the TV news camera that’s capturing the real world. He focuses on the backdrop, on reality, and then changes the focus in the same shot to what’s on camera.

For example, when Louis films the cops shooting at the murderers in the restaurant, Louis’ camera lens is in focus—we see the simulated on-screen view of the scene. But when Gilroy cuts to Rick filming the same scene, what’s in focus is the real scene, and not the camera lens. (See the two images below.)

It’s as if Rick cares about reality, while Louis only cares about what’s on film, which is not real, and which is, for him, a consumable product.

So maybe filmmaking, like the TV news industry, encourages psychopathy. This is a question that Nightcrawler brings up, although I’m not sure what its final conclusion is. It does seem that the final scene, where Louis is in charge of a growing production company, indicates that psychopaths do rise up the corporate ladder to run or manage media industries.

In its opening montage, the film plays with the differences between reality and the simulated world of TV news The introduction to the film shows us about twenty static shots of Los Angeles, with the main theme music playing over them. The shots of the streets are empty at night, with no humans until the eleventh shot. In the opening shot, there’s a billboard with nothing on it—a blank screen. If we saw this blank screen at the end of the movie, we might be relieved, given that the TV news throughout the movie fills blank screens with violent, gruesome images.

Why does this movie open with a montage of over 20 static shots in a row?

I think Gilroy is showing us that there’s a wider, greater Los Angeles that’s not being filmed by TV news—in fact, it’s being totally ignored by it. And there’s beauty to LA, over and against the horrific, graphic violence that the news depicts. If all you did was watch the news, you’d think that L.A. was simply a bloodbath filled with accidents and crime.

Yet the opening twenty shots of this movie counter that impression: at night, LA is quiet, charming, and aesthetically interesting, if not downright tranquil and pleasing.

Louis ignores all of the varied possibilities of the city, choosing only to film the few sensational events that rarely occur. Viewers of the news miss out on all of the opening shots that Gilroy shows us, seeing only the violence depicted in Louis Bloom’s camera work.

One more thing about Louis: the way he talks is quite unique. Most people, I hope, will notice that Bloom speaks in business clichés. His lines seem as if they are ripped from business textbooks or managerial self-help books on leadership.

At one point he exclaims, while chiding Rick, that “communication is the #1 key to success!” Later, as he and Rick run from a crime-scene, Louis tells him that “there’s no way to have better job security than to make yourself an indispensable employee!”

And when Rick is dying, Louis says to him, “I can’t jeopardize my company’s success to retain an untrustworthy employee.” Who says that to a dying man, except a man who speaks like a business textbook?

So Louis not only ignores ethics and aesthetics, his linguistic style is extremely limited. His language is one of economic transactions, and only of economic transactions, even when he is talking to would-be friends.

This, for Nightcrawler, is the picture of the business-minded filmmaker: a ruthless person who will film anything for a profit, who will say anything for more profit, and who has no ethical standards of any kind to keep him in check. It’s an extreme depiction, perhaps, but to break our trust in news media, the film has to do this.

I observe, in conclusion, that Nightcrawler is a the rare two-act movie with a prologue and epilogue. It has no third act, as nearly all movies do. Where is the third act in which Louis confronts the massive problems he’s created? Almost anyone creating this film would’ve chosen to enhance the presence of the police detective who questions Louis in the end, making her the moral voice that would confront Louis in Act 3.

But this is not a movie where the moral voices have any power at all.

The lack of a third act has to do, I think, with the unsettled conclusions that Nightcrawler makes. It forces us to go from the movie-world to our own lives, realizing that the problems that Nightcrawler has described are as yet unameliorated, if not unnoticed.

We have Louis Blooms everywhere, in power, especially in media organizations. We have famous frauds posing as TV journalists, who always make excuses for their bad actions, but who also lie to make themselves look better. Some of them promote images that manipulate and harm us.

As Werner Herzog says, we must have adequate images, at least, but Nightcrawler tells us that journalism is not providing those images. In fact, it’s providing us with the exact opposite.

Louis Blooms are also on the rise online, writing and commenting and filming videos for the sake of attention and profit. What are we going to do about their ever-growing presence in our lives? That to me is the question of Nightcrawler’s final shot.

As Louis’ two news vans drive off in that final shot, blanketing Los Angeles with their camera coverage, we know that Los Angeles is different now. It won’t have the sparse beauty of the opening montage in the film’s beginning. Instead, it will have cameras looking for, and perhaps creating, mayhem and chaos.

The end of this film is a call to action. What are you, the viewer, going to do about your viewing? What do you want to look at, and why?

I feel the weight of these questions always at the end of Nightcrawler. The movie tells me that, when I really want to see the latest tragedy on-screen, maybe I’m part of the problem. Maybe my desire to seek sensational news is what helps propagate the Louis Blooms of the world.

And if I’m not careful, Louis Bloom will film me, just like he filmed his friend and employee, Rick.

Thank you for writing on this memorable movie. Gilroy’s goal of filming “loading dock LA” was really successful, I thought. At times the night scenes reminded me of Lang’s _M_, but I think you are right about Gilroy offering scenes suggesting a more neighborly LA. The movie make me think of arguments like Millard’s _Destiny of the Republic_, and Berman’s _All That Is Solid Melts Into Air_, about how modern culture can encourage some kind of pin balling among ambition, obsession, fear and resentment. Did you find a contemporary political question in the movie, paralleling the moral questions you suggest?

thank you. I have had others tell me those opening shots of “Nightcrawler” are haunting, because they are dark, empty, foreboding, etc. So I think they can go both ways. There must be a political aspect to this film although it escapes me, except that the moral is always connected to the political in some way. If you have suggestions, I would love to hear it. (Maybe “the court jester” angle? Because TV is entertainment, or the “court jester” of the republic, and that’s the role that TV news is pursuing? Just thinking as I type.)